Why do boys harass and intimidate each other this way? Angela Phillips explained it like this: "The effect of intimidation is to drag other children down to the same level of powerlessness, through fear. A child who lives in fear is unable to learn. The bully has then reduced his victim to his own dysfunctional level." That is exactly what I was trying to do with Denny. I just picked the wrong victim, that's all.

Here's another reason why bullies bully. The Journal of Developmental Psychology reported a study of 452 boys in the fourth, fifth, and sixth grades. It revealed that those who taunted weaker peers and were aggressive and rebellious at school were often the most popular with their classmates. Raw power and audacity in boys are the characteristics kids tend to admire. Dr. Phillip Rodkin of Duke University explained why. He said, "These boys may internalize the idea that aggression, popularity, and control naturally go together, and they may not hesitate to use physical aggression as a social strategy because it has worked in the past." In other words, bullies are rewarded socially for harassing kids who are below them in the pecking order, which probably explains why many of them do it. By the way, other studies showed that bratty and rebellious behavior among girls did not result in greater popularity. Only boys are admired for breaking the rules. One or more of them could belong to you!

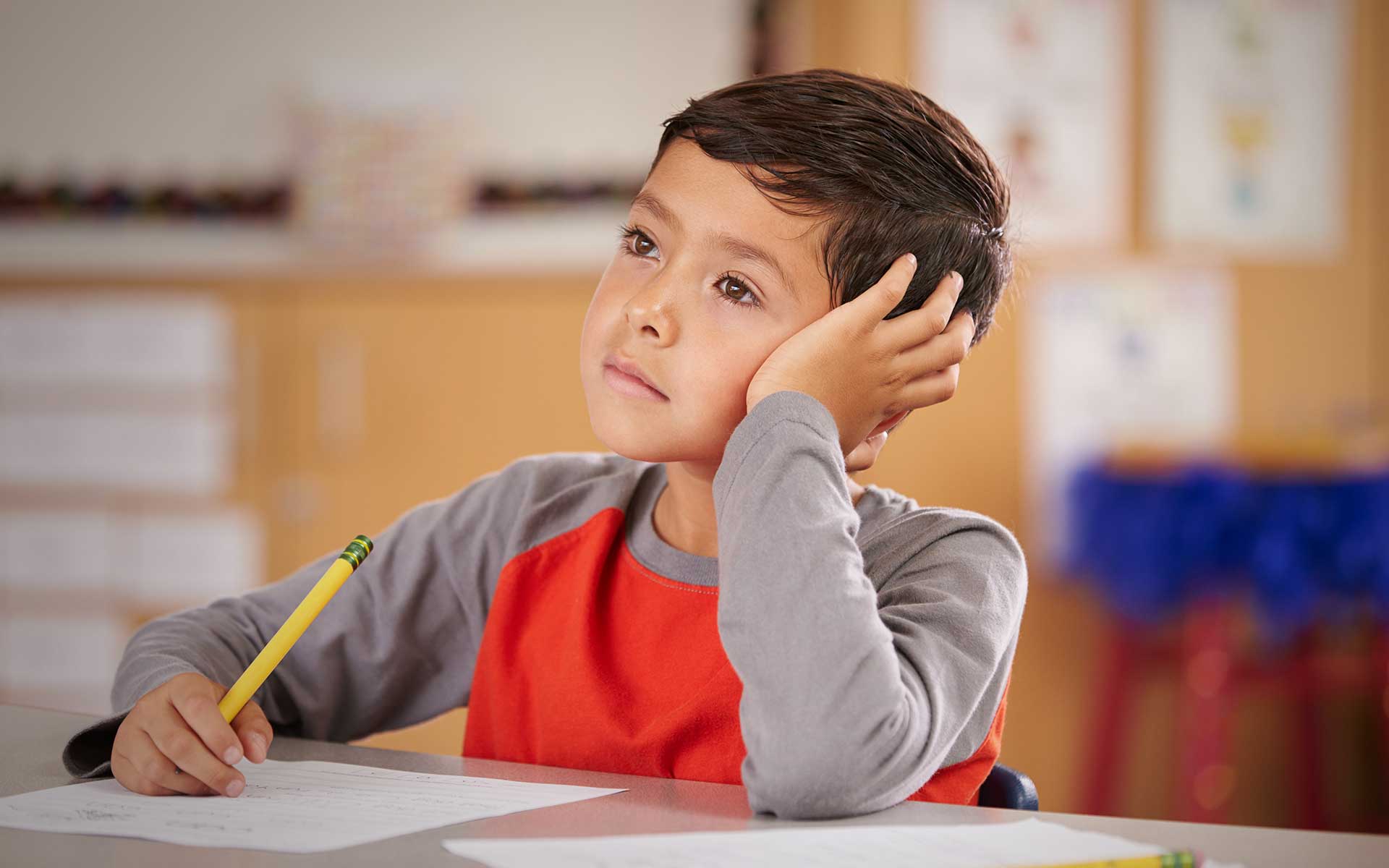

Whatever the reason, there are plenty of young bullies around to do their dastardly work. A study by psychologist Dorothy Espelage revealed that 80 percent of students take part in bullying, and 15 percent of seventh and eighth graders say they bully someone regularly. In an older study, boys were found to be four times as likely as girls to be responsible for physical attacks and far more likely to be victims of attacks. In a study sponsored by the Kaiser Foundation, 74 percent of eight-to eleven-year-olds, and 86 percent of teens, report being teased or bullied by their peers. One child in five is frightened in the classroom. It is a major problem for boys on campuses today. It also plays a significant role in the bloody violence that continues to distress the nation. In the past four decades, there has been a 500 percent increase in the rates of homicide and suicide. I am convinced that many of those who kill themselves, and who kill others, suffer from wounded spirits. Andy Williams, the young gunman who killed two of his classmates at Santee High School, was taunted relentlessly for having an "anorexic body." Some kids can pass off this kind of ridicule, but for others it turns into a rage that lasts for a lifetime.

Those who turn violent or behave in other antisocial ways often come from the bottom of the social pyramid. Adrian Nicole LeBlanc, author of an article entitled "The Outsiders," provided some valuable insight for us about bullying as follows:

The traditional hierarchies operate [in school]: the popular kids tend to be wealthier and the boys among them tend to be jocks. The Gap Girls-Tommy Girls-Polo Girls compose the pool of desirable girlfriends, many of whom are athletes as well. Below the popular kids, in a shifting order of relative unimportance, are the druggies (stoners, deadheads, burnouts, hippies or neo-hippies), trendies or Valley Girls, preppies, skateboarders and skateboarder chicks, nerds and techies, wiggers, rednecks and Goths, better known as freaks. There are troublemakers, losers and floaters—kids who move from group to group. Real losers are invisible.

To be an outcast boy is to be a "nonboy," to be feminine, to be weak. Bullies function as a kind of peer police enforcing the social code. The revenge-of-the-nerds refrain—which assures unpopular boys that if they only hold on through high school, theroster of winners will change—does not question the hierarchy that puts the outcasts at risk. So boys survive by their stamina, sometimes by their fists, but mainly, if they're lucky, with the help of the "family" they've created among their friends.

LeBlanc continued with revealing excerpts from an interview with a boy named Andrew, who was at the bottom of the heap:

"First people harassed me because I was really smart," Andrew says, presenting the sequence as self-evident. "I read all the time. I read through math class." Back then, in middle school, he had the company of Tom Clancy and a best friend he could talk to about anything. He says things are better now; during school, he hangs out with the freaks. Yet the routine days he describes sound far from improvement—being body-slammed and shoved into chalkboards and dropped into trash cans headfirst. At a school dance, in the presence of chaperones and policemen, R. lifted Andrew and ripped a pocket off his pants. "One day I'll be a 'faggot,' the next day I'll be a 'retard,'" Andrew says. One girl who used to be his friend now sees him approaching and shouts, "Oh, get out of here, nobody wants you!"

Andrew joined the cross-country team but the misery trailed him on the practice runs. He won't rejoin next year although he loves the sport. Recently he and some other boys were suspended for suspected use of drugs. According to Andrew, he used to earn straight A's; now he receives mostly C's and D's. He does not draw connections between the abuse and the changes in his life.

Neither does Andrew tell his parents. He believes they think he is popular. "If I try to explain it to my parents," he says, "they'll say: 'Oh, but you have plenty of friends.' Oh, I don't think so. They don't really get it." His outcast friends, however, do.

One of them is Randy Tuck, a 5-foot-4-inch sophomore with a thick head of hair and cheeks bright red with acne. He rescued Andrew from a "swirly" (two boys had him ankle up, and headed for the toilet bowl).

Andrew says that the ostracizing "does build up inside. Sometimes you might get really mad at something that doesn't matter alot, kinda like the last straw." He could understand the killers, Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris, if their misery had shown no signs of ending, but Andrew remains an optimist. After all, there are some people who have no friends.

It is not difficult to understand how boys with wounded spirits—the freaks and the geeks and the nerds and the dorks and the dweebs—can break loose under intense pressure and do unthinkable harm to others. I'm not excusing or justifying their behavior, of course. Most students journey through this difficult time without resorting to violence. Some, however, harbor such hatred that they shoot not only those who have taunted them but everyone else in sight. Then they turn the guns on themselves as the ultimate act of self-hatred. In nearly every instance of random violence on school campuses, young perpetrators have been ridiculed and harassed by their peers. As mentioned by Andrew, this is what happened at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, on that tragic afternoon in April 1999. Twelve students and a teacher were murdered before the two seventeen-year-old gunmen committed suicide. While they bear the full responsibility for the massacre, one cannot study the underlying circumstances without seeing evidence of rejection by the more popular kids. As they were killing their classmates, Klebold reportedly shouted, "This is for everyone who teased us." Harris said, "Your children have humiliated me. They've embarrassed me. They will all be dead, [blankety-blank-blank], they will all be dead. I am God and I determine what is true." Pent-up anger obviously boiled over and resulted in many deaths. It is becoming a familiar pattern.