The challenge: Fragile freedom

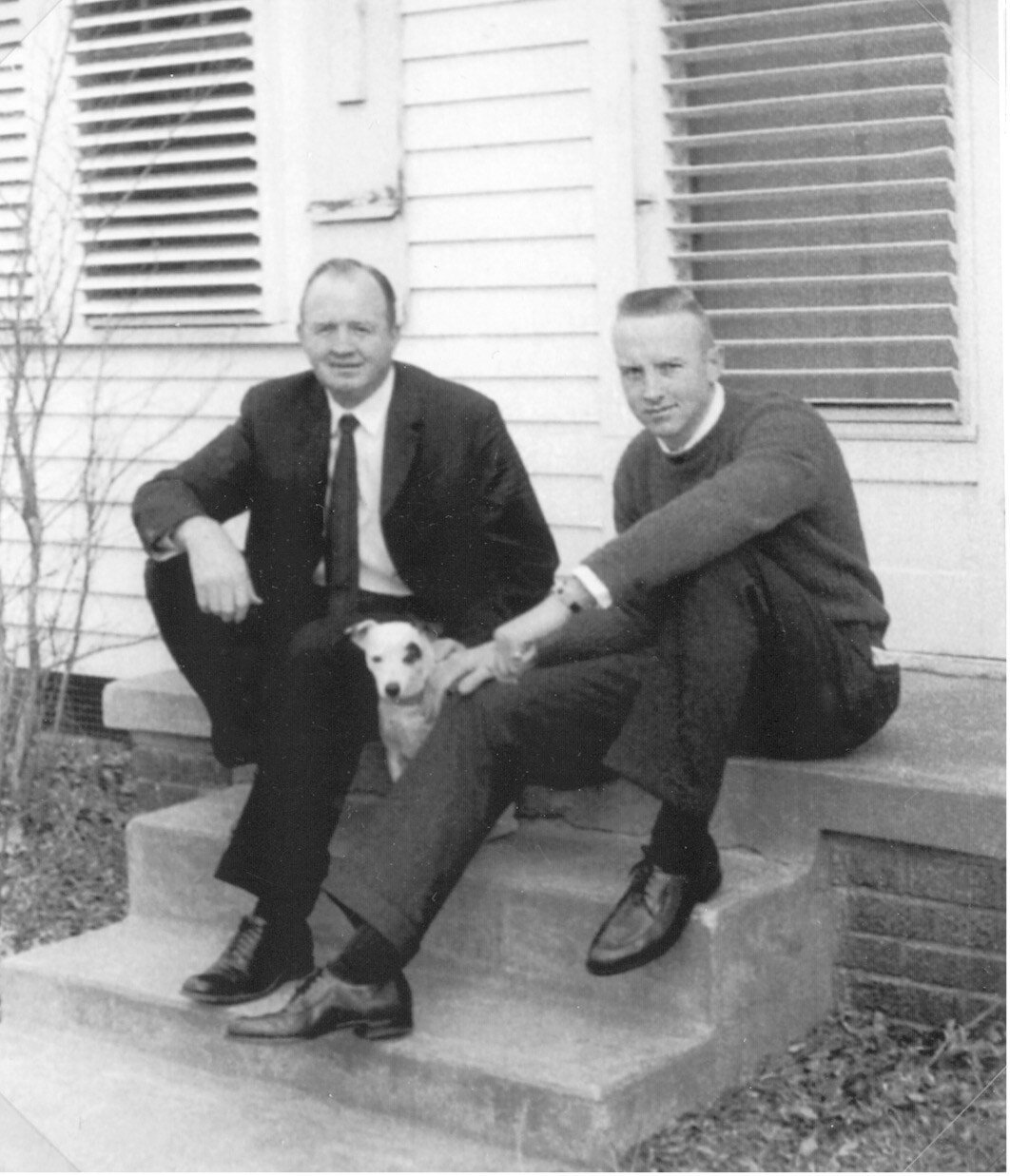

We remember the day well. Papa John wore his best poker face as he climbed carefully through the bomb-bay doors and into the fuselage, his grandchildren scrambling close behind. But it had to have been an emotional moment for him at the Fantasy of Flight museum in Florida. During World War II, he served with the 450th bomb group, a nose gunner in a B-24 Liberator, making runs from Italy into southern Europe. Unlike many others, he returned to wed, raise a family and watch his children raise families of their own.

Even with its bomb racks empty, the bomb bay was surprisingly cramped. Between the racks, the only way forward to the flight deck and to Papa John's former battle station was a narrow girder. Negotiating that, then hunching down and crawling forward, we watched him advance as far toward the nose turret as his creaky knees would let him, just far enough to brush aside a patch of spider webs and peer inside through its double hatch.

He certainly had a good view, as far forward as one could be in that airplane, with only a bubble of glass to protect him from the frigid, onrushing air. How did he fold himself and all his gear into that tiny space for endless hours? How did it feel to be shot at the first time, to see and hear flak ripping through the body of the plane? What did it feel like to climb back inside for a second, then a third mission? Was he able to expel the thought that the next mission might be his last?

As with most others who make it back from war, it is rarely easy to share details about those days. Even if an opportunity presents itself, the story is difficult to tell. Wanting above all to be accurate, how does one weave a complete and coherent story out of a collection of memories, some vivid and some vague? And how do you tell your story knowing that it is only a small part of a colossal undertaking?

More often than not, veterans' experiences are forgotten. It is our duty, not theirs, to collect and preserve their stories, and it is always right to recognize their sacrifices and thank them by working at home to restore and maintain an America of virtue.

We all know the words "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

Although it's true that these truths are self-evident, it's important that we never forget that they are not self-actualizing. Man was made for freedom but not born into it.

As Ronald Reagan stated in 1961:

"Freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction. We did not pass it to our children in the bloodstream. It must be fought for, protected and handed on for them to do the same, or one day we will spend our sunset years telling our children and our children's children what it was once like in the United States where men were free."

The hope: Wholehearted commitment

If we as a nation ever take our freedom for granted, we will lose it. As we consider how to honor our lost servicemen and -women this Memorial Day, it is only appropriate to look to the story of the greatest sacrifice of all time.

Jesus Christ won the most decisive victory and secured the fullest freedom we can experience this side of heaven. But it didn't come without a price. In the Garden of Gethsemane, just before he was crucified, he prayed, "My Father! If it is possible, let this cup of suffering be taken away from me. Yet I want your will to be done, not mine" (Matthew 26:39).

No soldier, guardsman, Marine, airman or sailor desires death. But every single one of them has made the ultimate sacrifice already: They have laid down their own wills for a higher one. For many, the sacrifices of their wills meant, or will mean, the laying-down of their lives as well.

Christians take Communion to remember Jesus' life offered up on our behalf, but the sacrament is intended for more than remembrance. In the same way, Memorial Day is intended to be more than a day for remembering.

Before we take Communion, we are told to search our hearts. What sins have we not brought to the light? Whom do we need to forgive? From whom do we need to seek forgiveness? Communion is an invitation to survey the true conditions of our souls and initiate reconciliation and healing within the church.

What better way is there to honor those who died to preserve this country than to stop and consider its condition? How have we taken our freedom for granted? Where is tyranny or oppression sneaking in, and how can we eradicate it? What divides us as citizens, and how can we strengthen our national bond? How are we teaching our children to value freedom?

We should not approach Memorial Day in an unworthy manner. So let us examine ourselves and commit wholeheartedly to strengthening the freedoms and virtues that mark our great country. In this manner, we will truly honor those who have given their lives.

First appeared in The Washington Times.